Introduction

Laldighi– the 5.7-acre rectangular water body in Kolkata’s B.B.D. Bagh was not only the historic blue centre of the erstwhile Calcutta, but it also continues to be the nucleus of the city’s administrative district for more than three centuries now.

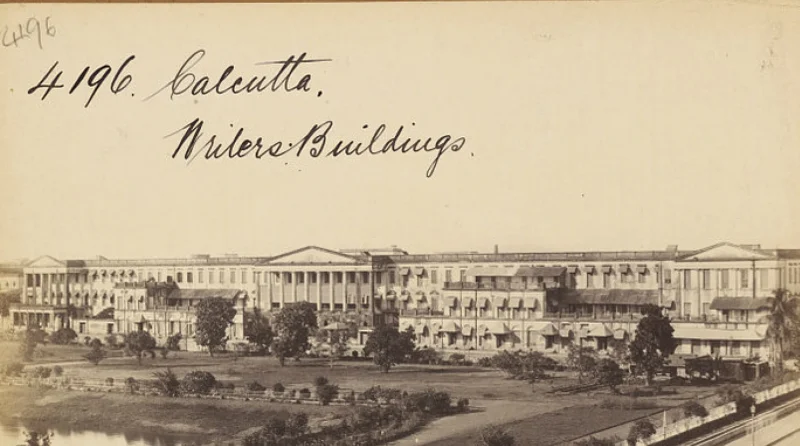

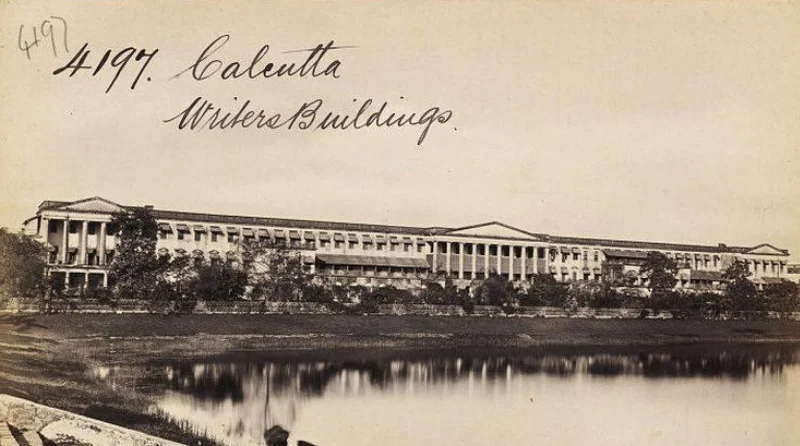

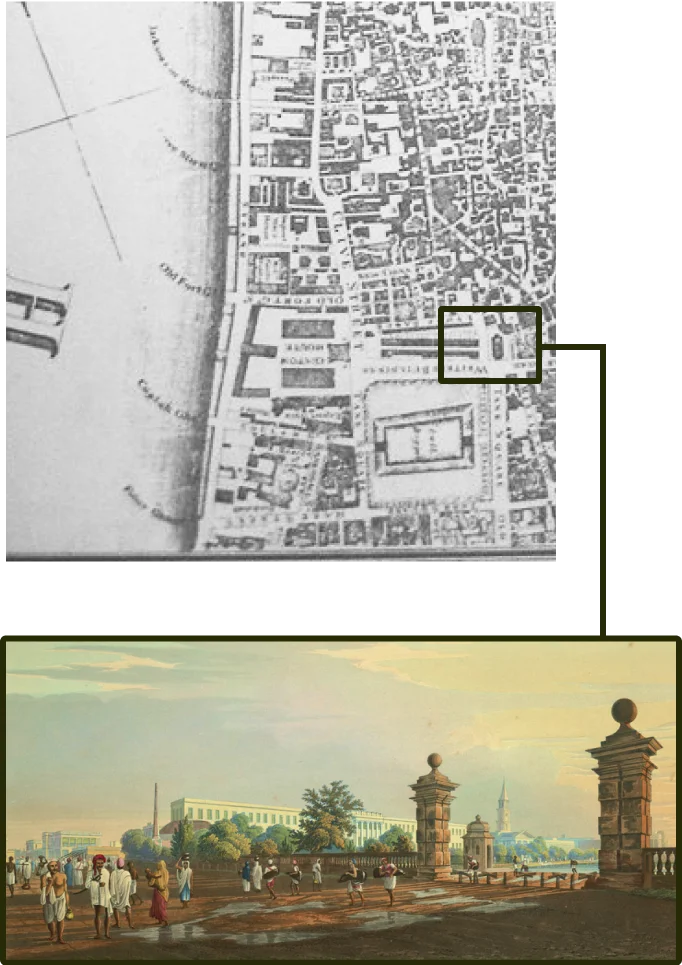

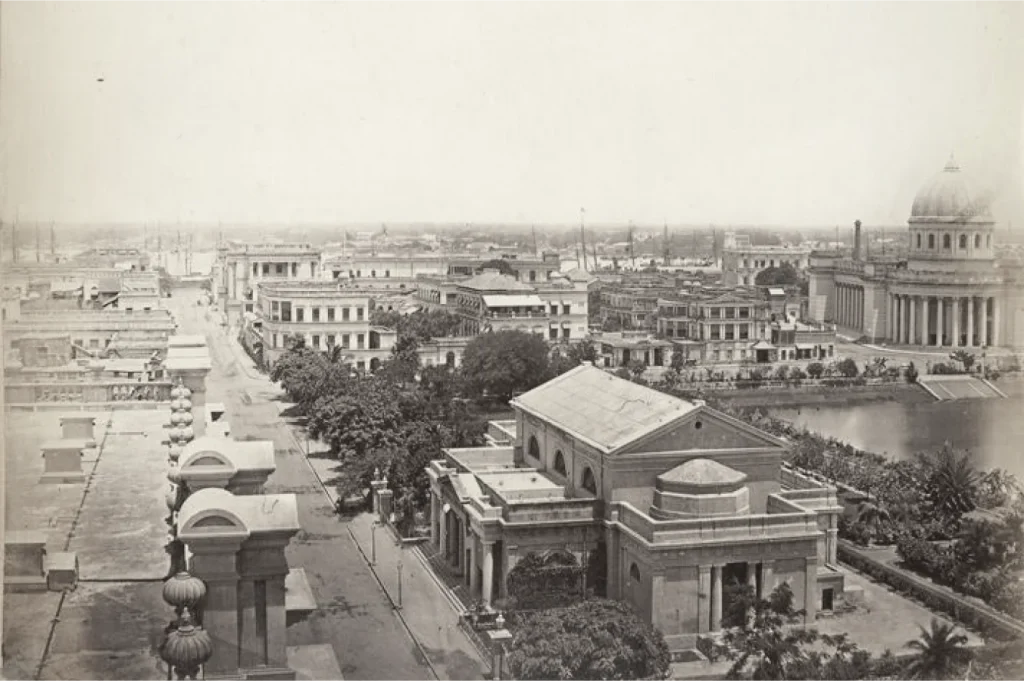

Laldighi is surrounded by several listed heritage buildings. Writers’ Building (secretariat of the state government) on its north, General Post Office (GPO) (that stands on the footprint of the Old Fort) on its west, Standard Life Assurance building and Dead Letter Office on its south and the Currency building on the eastern side are some of the most prominent ones. The Royal Exchange (former residence of Robert Clive, now housing the Bengal Chamber of Commerce), Town Hall, High Court, Governor’s House, and St John’s Church are also in its close vicinity.

“Laldighi was not only the historic blue centre of the erstwhile Calcutta, but it also continues to be the nucleus of the city’s administrative district for more than three centuries now.”

Consequent to the initiatives of Action Research in Conservation of Heritage (ARCH) and the Indian National Trust for Arts and Cultural Heritage (INTACH), this square was declared one of the 100 most endangered sites of the world by the World Monuments Fund on 24th September 2003. Once opulent with verdant greenery on all sides, Laldighi has, slowly but steadily, lost its green open spaces on the north, east, and south to the ever-demanding urban utilities that have established their concrete presence on these sides. The western flank towards the General Post Office is the only sizable open space remaining now.

The Beginning

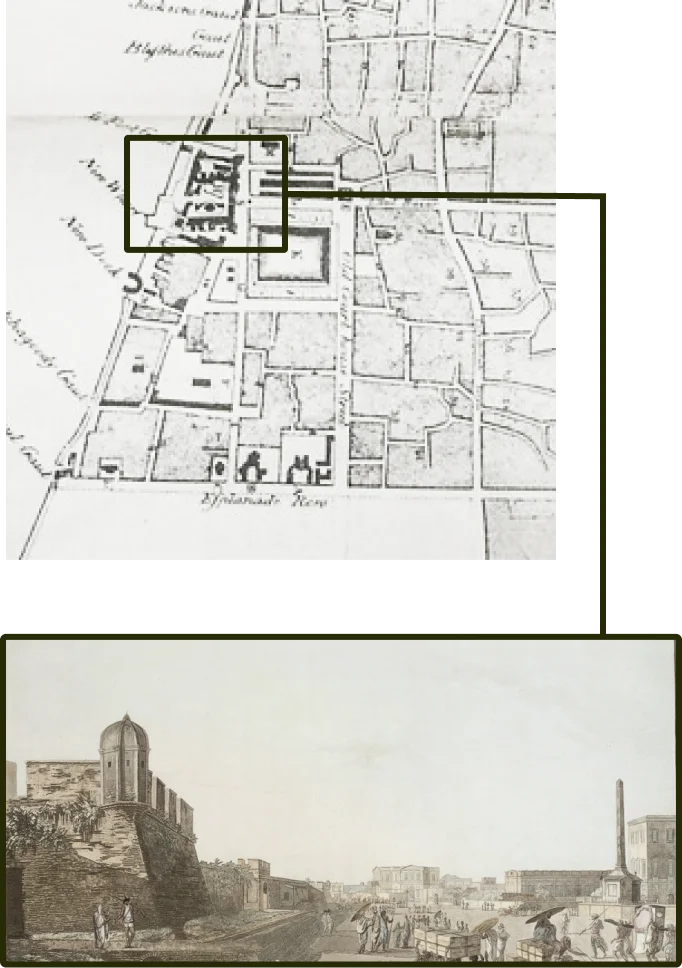

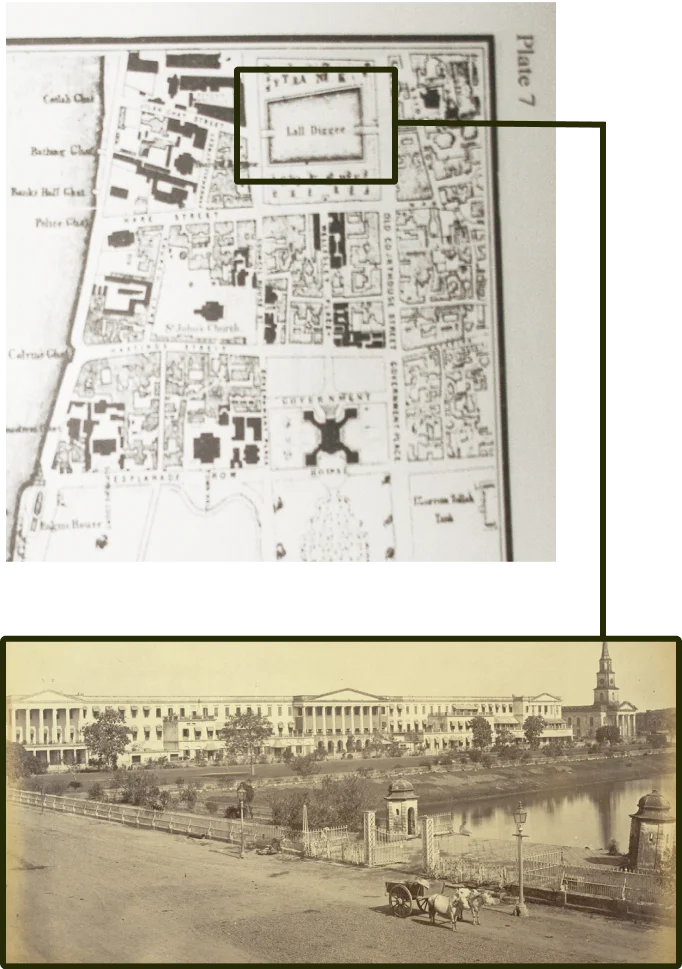

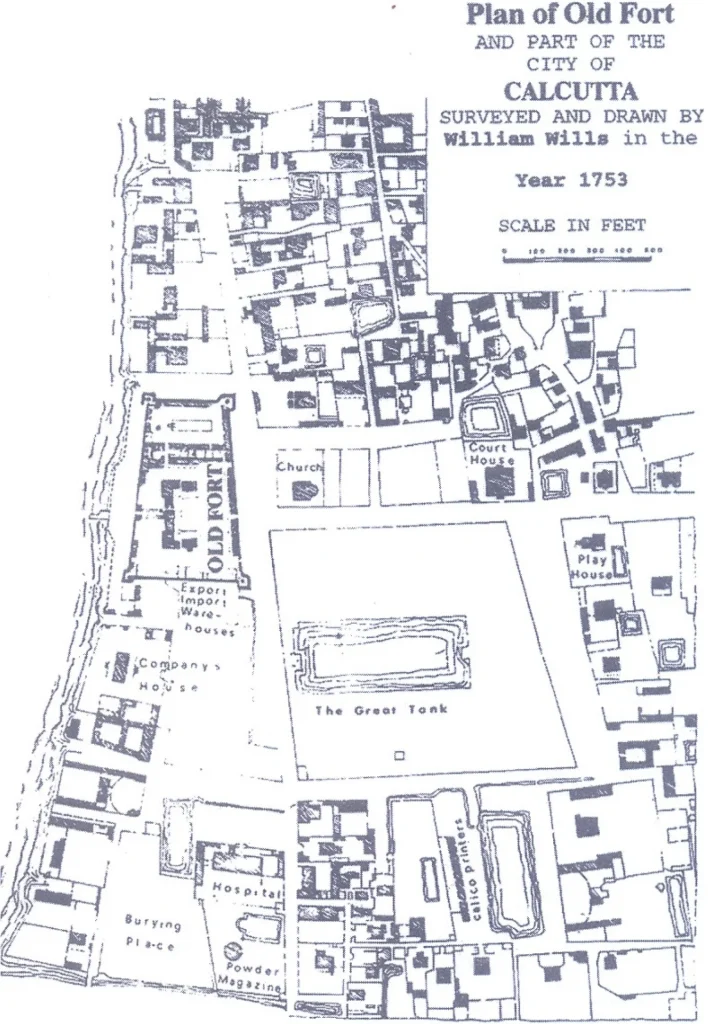

Right adjacent to the place where Job Charnock had established his trading post in 1690 and where the old Fort William was later erected (begun in 1698 & completed in 1706), Laldighi served as the blue centre of the British business settlement, then known as the ‘White Town’. Laldighi was popularly stated to be ‘in the middle of the city’ during the 18th century.

“Plan of Old Fort (1753): Map drawn by William Wills where Laldighi mentioned as ‘The Great Tank’ ”

Origin of the name Laldighi (Red tank)

In Bengali language, Laldighi means ‘Red Tank’. There are three schools of belief regarding how such a name was derived:

- The water got red hued during ‘Holi’ or ‘Dol’ festival played near the Shyam Rai temple of the local zamindar Sabarna Roy Choudhury’s family He also owned a kutchery (court-house) nearby that was first rented and later purchased by the British East India Company.

- The red coloured old fort got reflected in the water and hence the name.

- A businessman named Lalchand Basak of Dihi Kalikata had excavated the pond and thus the tank came to be known as Laldighi after him.

Many a name & many a use

Initially referred to as the ‘Green before the Fort’ by the British, it was named ‘the Park’ and the ‘Great Tank’, followed by ‘Tank Square’, and eventually, ‘the Dalhousie Square’ in 1865 in memory of Governor General (1847-1856) Lord Dalhousie (1812-1860). In the 1960.s, the square was renamed as Benoy-Badal-Dinesh Bagh or B.B.D. Bagh, in short. The park and the tank together supplied plant and fish produces to the Company, while serving as the main source of drinking water until the introduction of municipal water supply. The Laldighi ground was the recreational hotspot of the time, where the British took an evening stroll, enjoyed the breeze and also shot wild fowls once a while.

Laldighi in 18th – early 20th century

Laldighi in recent times

A Black hole in history

The Battle of Laldighi

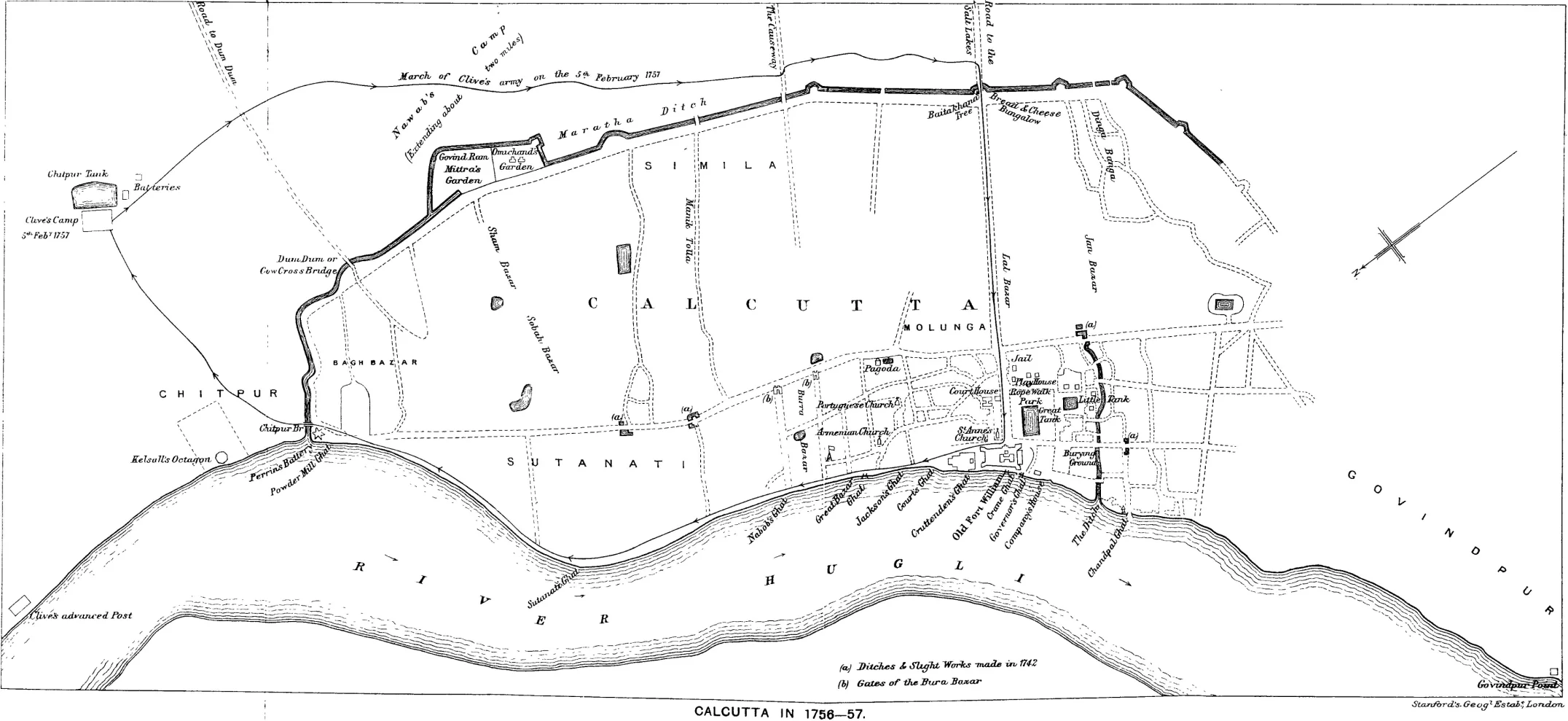

The peaceful ambience of the ‘Park’ changed into a violent scene of battle in 1756, when the forces of the Nawab of Murshidabad rampaged through the town and captured Calcutta on 20th June 1756. St. Anne’s church (built 1709), where the Rotunda of the Writers’ building now stands, and the old Fort William suffered great damage. This battle is associated with the much-contested Black Hole tragedy.

Fortunes turned in 1757 and Calcutta was recaptured by Lord Clive in the Battle of Plassey, Murshidabad by defeating Siraj-ud-daulah, the last Nawab of Bengal. The old fort was reestablished in 1758.

The next nearly two centuries saw Calcutta emerge as the ‘City of Palaces’, marked by commissioning of several landmark institutions – Asiatic Society of Bengal (1784), Governor’s House (1803), Imperial Museum renamed Indian Museum (1814), Agri-horticultural Society of India (1820), General Post Office (GPO – 1868), Central Telegraph Office (1876), and Victoria Memorial (1921) to name a few. The physical limits of the city expanded manifold. Laldighi & the square, however, remained mostly unchanged in terms of its physical fabric.

A comparison of the three maps of the years 1784-85, 1825-32 and 1855 reflect an evolution of the N-E corner of the Tank Square. While the Old Court House (or Kutchery) is seen in the first, it is replaced by the St. Andrew’s Church (1818) in the second map, and the last photograph shows the church spire dominating the northern skyline of Laldighi.

Survey maps showing evolution of the Laldighi environs

Interactive Map of Calcutta

Jaun Bazar

The landed estate of Rani Rasmoni (1793-1861), an able administrator, and founder of Dakshineshwar temple.

Lal Bazar

Laldighi

Named the Park and the Great Tank (there was a little tank close-by).

St. Anne’s Church

The first English Church, east of the old Fort Williams, where the Writers’ Building now stands

Old Fort Williams

The first foothold of the British East India Company on the eastern bank of River Bhagirathi-Hooghly.

Portuguese Church

Armenian Church

Burra Bazar

The great market place and traders’ hub

Sutanuti

Mission: (Un)impossible, 1930

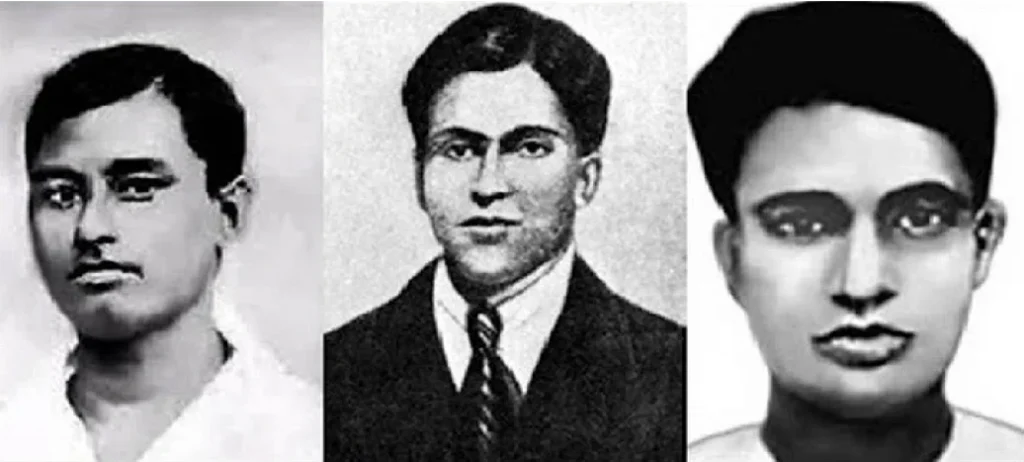

The valorous Trio

A quarter to two centuries since the battle of Laldighi, the same grounds became the backdrop for yet another historic event – a ‘revolutionary action’ as part of the Indian freedom movement. Inspired by Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose and with a burning desire to free their motherland, three Bengali brave-hearts in their teens/ early twenties, resolved to avenge the inhuman torture meted out to fellow freedom fighters in the prison.

Benoy Basu (22), Badal Gupta (18), and Dinesh Gupta (19), members of the Bengal Volunteers, marched into the erstwhile Secretariat (now Writers’ Building) on 8th December 1930. They were in impeccable western outfits to gain access inside. Benoy, Badal and Dinesh fulfilled their mission by fatally shooting Col. N. S. Simpson, the notorious Inspector General of Prisons, in his office. The valorous trio were martyred in the aftermath of this mission. Post-independence, Laldighi was renamed as Benoy-Badal-Dinesh Bagh (where’ bagh’ means garden/ park), B.B.D. Bagh, in short, to honour their supreme sacrifice and contribution in the freedom struggle.

Changing Skylines

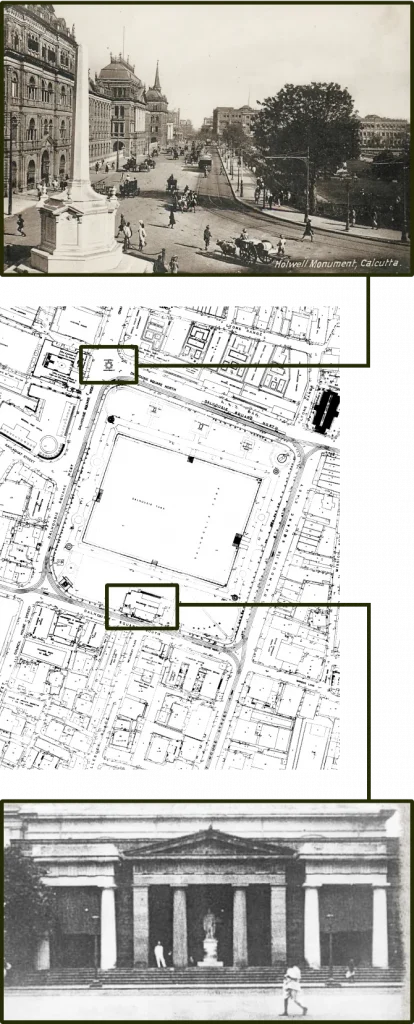

The 1910 Smarts survey map of Kolkata Municipal Corporation shows two structures near Laldighi that no longer exist:

- Holwell monument (encircled in the map by black dots) built in 1760 by G. Holwell and removed in 1940 to the St. John’s church grounds, mainly through Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose’s efforts

- Dalhousie Institute (encircled in the map by red dots), built in 1865 but replaced by the Telephone Bhavan building in 1950.

Looking west: Dalhousie Institute on the right side of the road. A glimpse of Laldighi is also seen in the extreme right.

With the demolition of the Dalhousie Institute in 1950 in favour of the ‘modern’ Telephone Exchange, the north-south vista connecting the two iconic seats of governance – Writers’ building in the north and the Governor’s House in the south- was permanently lost.

A blue-green space, a public place

Laldighi rejuvenation (2012-13)

In 2011, the newly elected State Government decided to restore Writers’ Building and also rejuvenate the Laldighi grounds (i.e. the western flank) that was being used for surface car parking. With due consideration of the historicity of the site and its environmental improvement, the landscape intervention emphasized on plantations along with spaces for passive recreation, keeping public safety and security in mind. A tactile site map signage of the area was added for information and appreciation of this historic urban core of the erstwhile Calcutta. Having mostly institutional land use in the surroundings, the Laldighi vicinities are exceptionally vibrant throughout the day but becomes quiet and desolate at night.

The W.B. Public Works Department, Kolkata Municipal Corporation, W.B. Fisheries Department, Calcutta Tram Company etc. extend urban services in and around the site. Office goers and citizens love to take a break amidst this refreshing green-and-blue void and enjoy the emptiness of the space, occasionally watching the upward motion of the jet fountain installed at the centre of the ‘dighi’. The tree canopies, fragrant flowers, cool breeze, silvery waters mirroring the sky, and the sheer wide openness induce a peaceful contemplative ambience. Three centuries of urban history hiding under the cover of this tranquility reveals only to the discerning who cares to listen to Laldighi’s soft murmurs.

Before and after images of Laldighi environs in 2012-13

Before

After

Before

After

Before

After

Before

After

Before

After

(source: Author)

Laldighi calling for attention

Till the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic, Laldighi used to be a convivial setting full of life and verdancy. Three years since then and about a decade of its restoration, Laldighi is yet to recover from the consequences of changed priorities in both public life as well as municipal governance. With the East-West metro passing by this ‘blue centre’ of Kolkata, we can only hope that it will regain its past glory once the metro rail becomes operational through its LALDIGHI halt.

References

- Amrit Mahotsav, Govt. of India, freedom-movement-detail. (accessed on 10.04.2023)

- Amrit Mahotsav, Govt. of India, unsung-heroes-detail.htm (accessed on 10.04.2023)

- ARCH & INTACH, (2005), Proceedings of the Workshop on ‘Conserving, improving and managing the historic city centre of Dalhousie Square, Kolkata’.

- Bardhan, S., (2011), Detailed Project Report on Laldighi for Kolkata Municipal Corporation.

- Busteed, H.E., (1908), Echoes front Old Calcutta: 1908 (4th edition).

- Chattopadhyay, M., (2013), Paschim Banger Porikalpita Nagarayan.

- Kundu Anil Kumar & Nag Prithvish, (1996), Atlas of the City of Calcutta and its environs, National Atlas & Thematic Mapping Organisation (NATMO).

- Netaji Research Bureau (accessed on 06.04.2023) Netaji Research Bureau

- Mukhopadhyay A., https://puronokolkata.com/2016/02/15/lal-dighi-lal-bagh-calcutta-1690/ (accessed on 10.04.2023)

- Ray M., Old Mirrors: Traditional Ponds of Kolkata, KMC, 2010.

- tuckdbpostcards (accessed on 06.04.2023)