Introduction

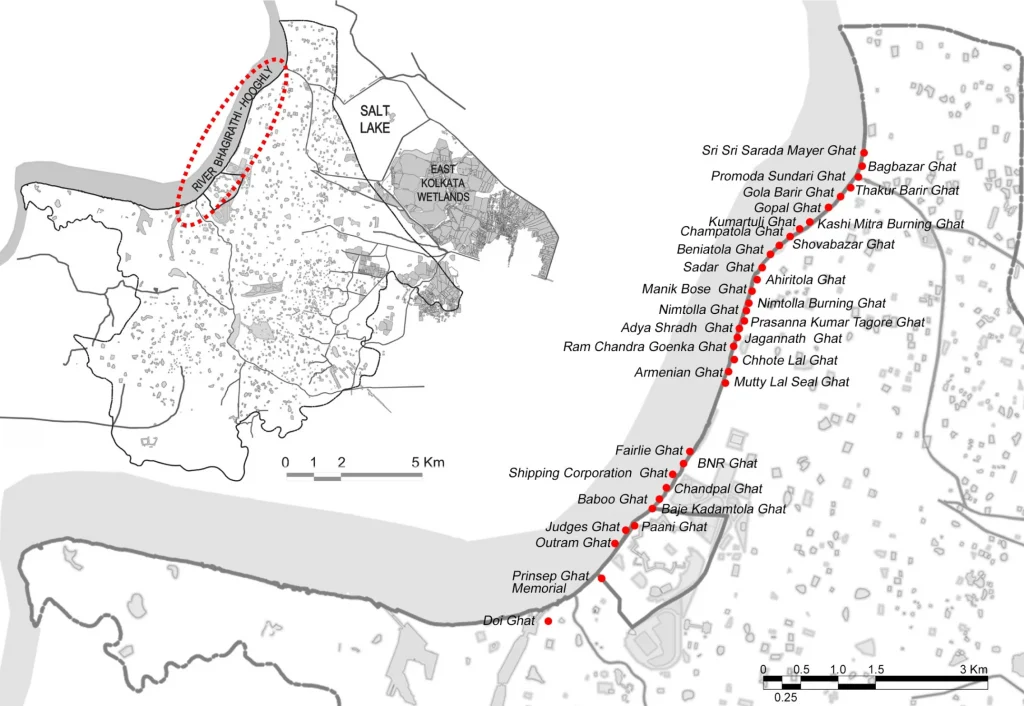

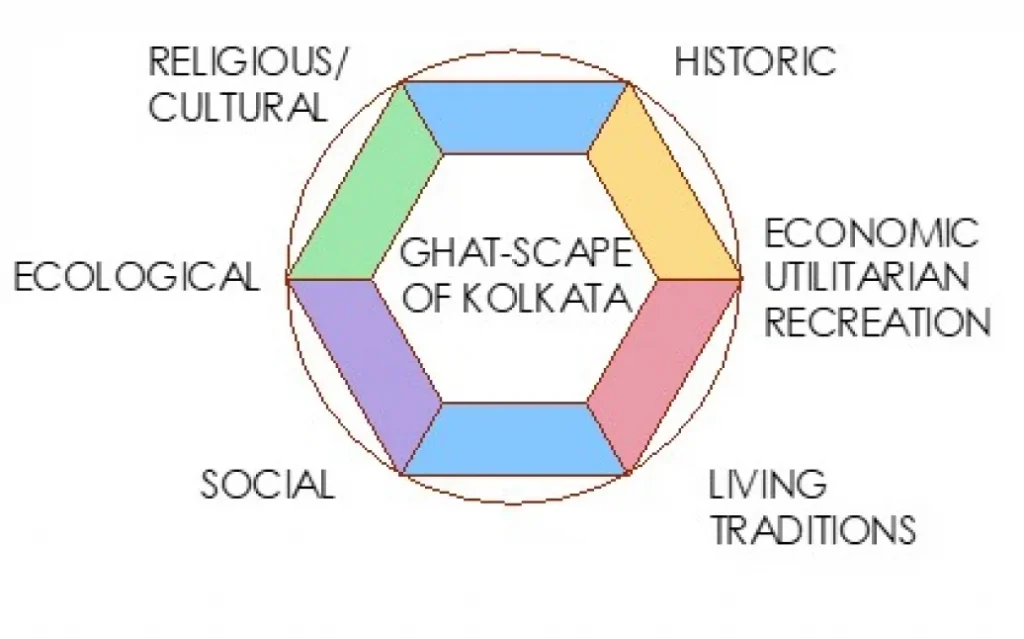

The focal point of this narrative is the unique cultural landscape created by the 40-odd ghats/ ghat-pavilions along the sacred Ganga river, locally known as R. Bhagirathi-Hooghly, flowing adjacent to the western edge of Kolkata. This lesser-known “ghat-scape” is highlighted, emphasising its cultural and ecological qualities, as well as the contemporary urban challenges it faces.

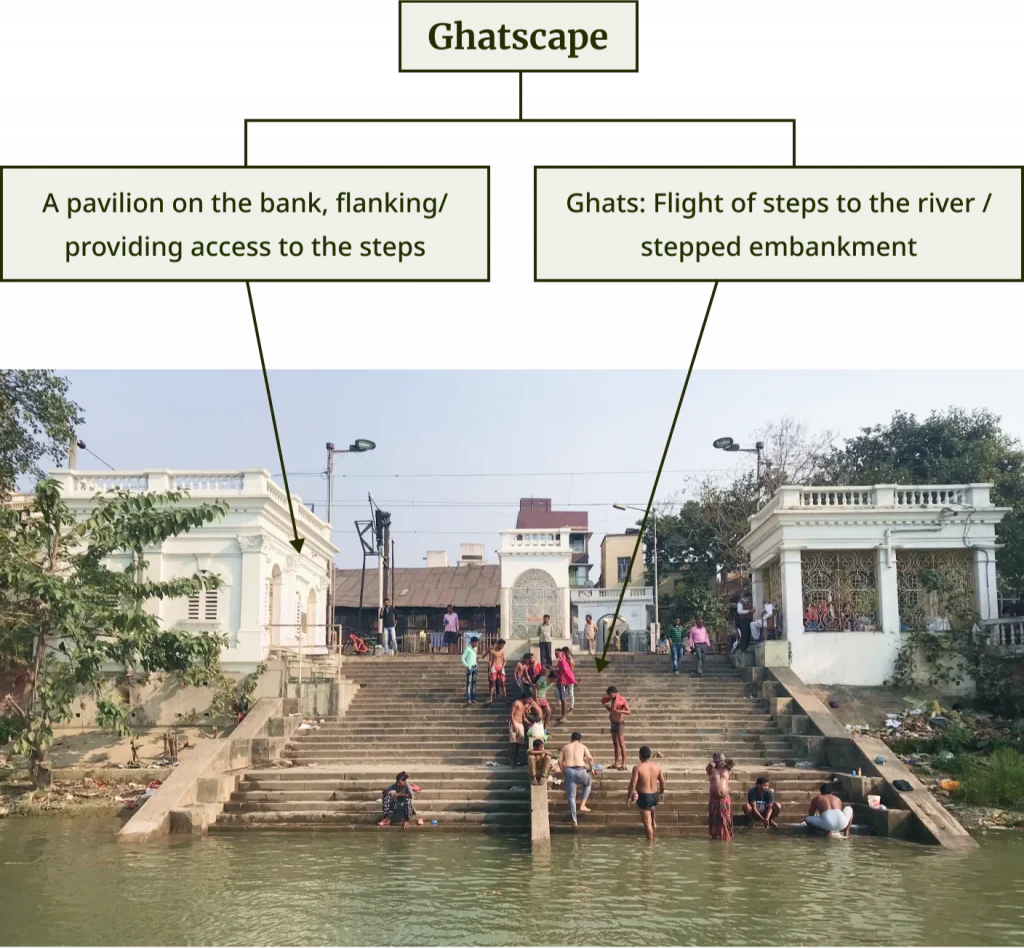

Ghats, which are a flight of steps descending to the water from the adjoining land, provide direct physical access to the river and, together with associated temples and pavilions, represent a unique cultural landscape lining a sacred river, generated by humankind over centuries in an attempt to reach the river. The Ghatscape encompasses various layers of geography, geomorphology, hydrology, ecology, and sacral, religious, social, and cultural veins, creating a landform with a typical Indian identity. The ghats along the Bhagirathi-Hooghly river have also given Kolkata a distinguished identity, supporting diverse activities such as social, recreational, transport, and industrial.

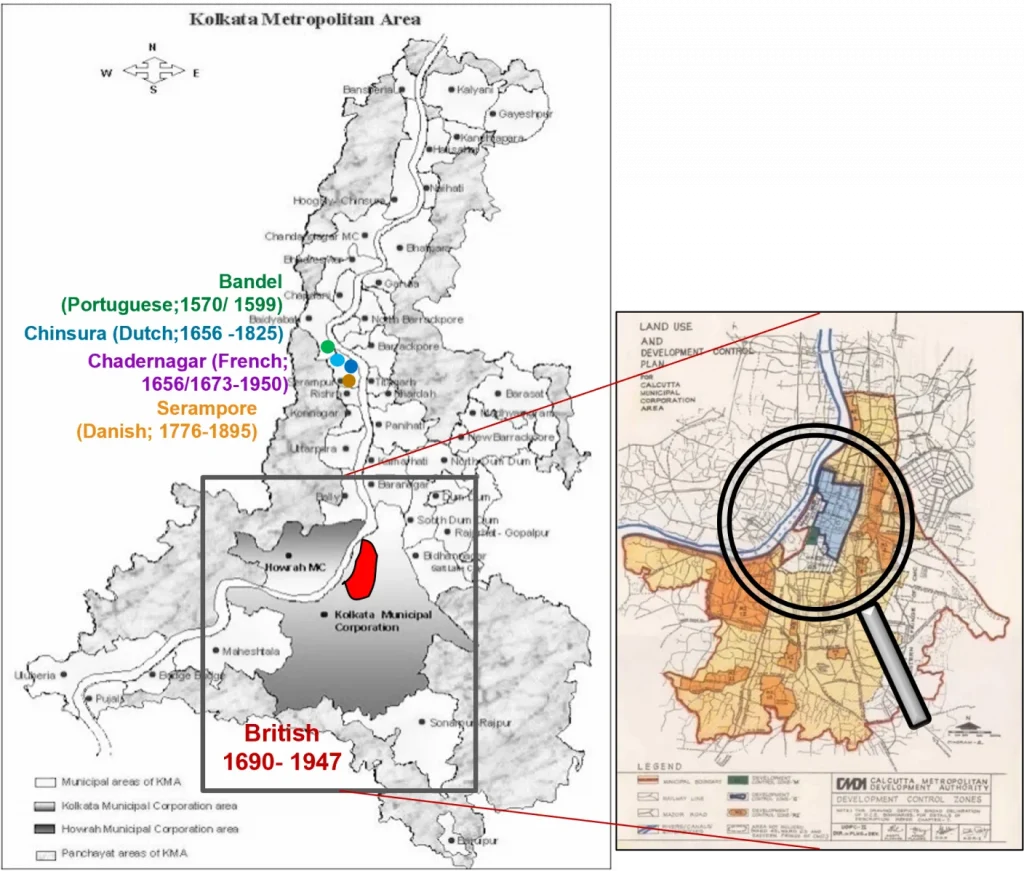

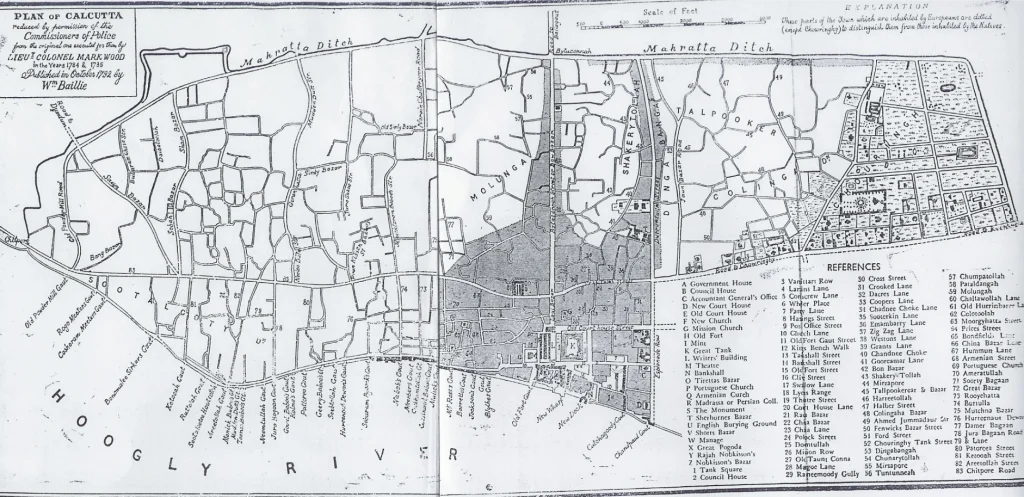

Regional Context: Little Europe on Ganges

Many settlements and cities grew up along a river basin since pre-historic times, but Kolkata is unique! India’s ties and trysts with Europe are long established. Spices, cotton, and the global slave-trade allured multiple European nations towards maritime trade, setting up numerous colonial port towns on the major trade routes. In the days of high colonialism during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, many European maritime powers explored various opportunities in India, including the unknown, forested, swampy region in the lower Gangetic delta, which later emerged as “Kolkata”.

Conflict of interest existed between the land-based trading communities, such as the Turks and the Armenians and the maritime traders such as the Western Europeans which shaped their destinies. While, to gain prominence and access over the lower-Gangetic Bengal, the Dutch, the Portuguese, the Danes, and the French established their colonies on the western bank of the river, the British traders explored their chances on the opposite banks and settled in Kolkata, and finally, successfully established the British empire with the nascent town as the future seat of power. With its strategic location and political influence, Kolkata became home to multi-cultural nationalities, contributing to India’s present “cultural capital” and its intangible culture, tradition, and heritage.

The ghat-pavilions exhibit an eclectic form of ghat-architecture, with varying scales, materials, designs, and functions. According to the classification of the UNESCO World Heritage Committee, the entire ghatscape can be classified as an “associative cultural landscape” due to its cultural-cum-sacral association with the river, presenting a unique historic urban fabric that connects people, places, culture, and faith. Because most functions, structures, and perceived characteristics have remained largely unchanged for over 60 years, the ghatscape qualifies as a Historic Cultural Landscape (HCL).

Ghatscape components

The Bhagirathi-Hooghly riverfront in Kolkata is dotted with ghats as well as ghat-associated pavilions, both constituting the unique ghatscape of Kolkata.

Dimensions of the Ghatscape

Historic

- Genesis of the metropolis of Kolkata

- Ghat-pavilions of historical and architectural importance due to their varied styles, use of materials, and symbolism

- Narratives associated with the riverfront and the ghat-pavilions

Ecological

- Management, maintenance & monitoring

- Flood control, supply of drinking and daily need for water

Religious/Cultural

- Tarpan – holy bath on the occasion of Mahalay, the first day of Durga puja

- Cremation Rites and rituals on demise of a near one

- Ganga-arati – worshipping the Goddess Ganga with oil-lamps

- Immersion of clay idols after the religious festivals

Social

- Social gatherings

- Storytelling by locals through ‘Ghat’/ heritage walks

- Wrestling and body massage

Economic/Utilitarian/Recreation

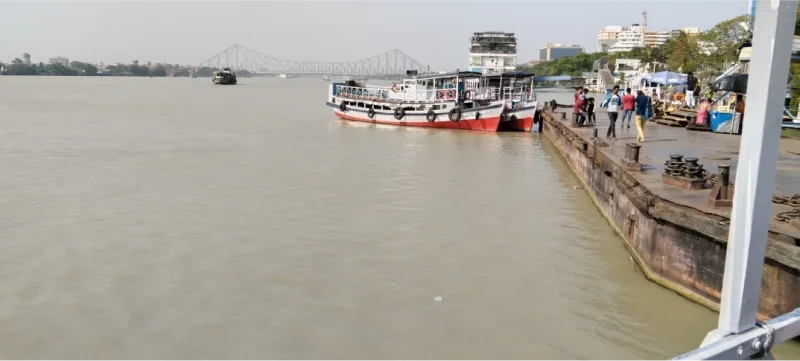

- Riverine trade and transport

- Flower market

- Ferry service

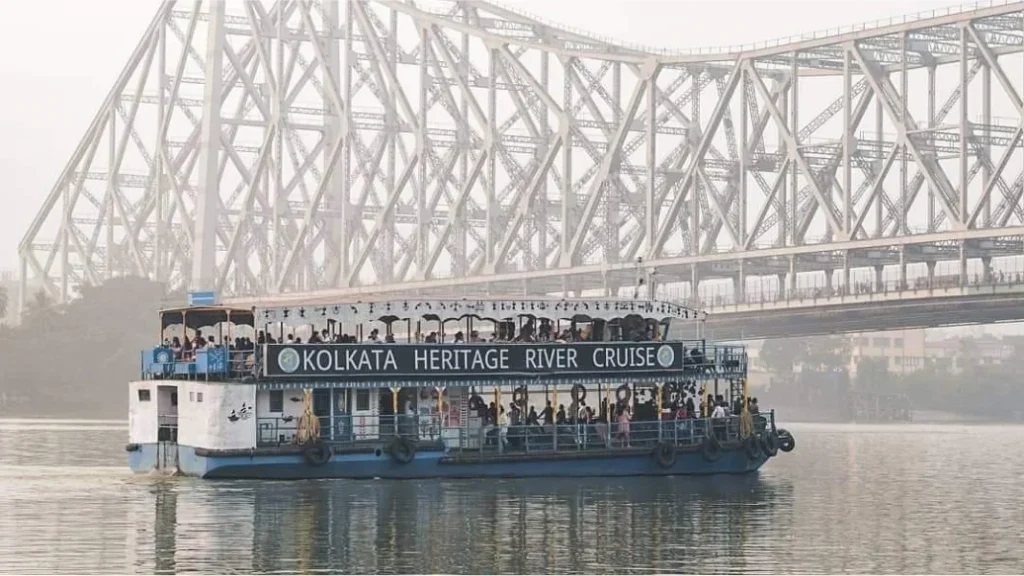

- Walkways, landscaped parks, boat rides, river cruises

- Minor trades/livelihood: Barbers, tea stalls, clay-idol making

Life in the Ghatscape

The river and the ghatscape offer a glimpse into the socio-economic and cultural character of the community.

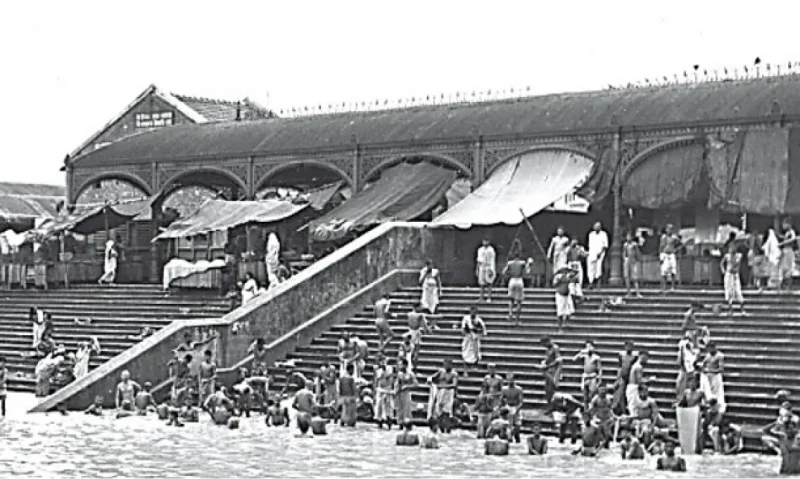

Religious

(Source : Sukrit Sen)

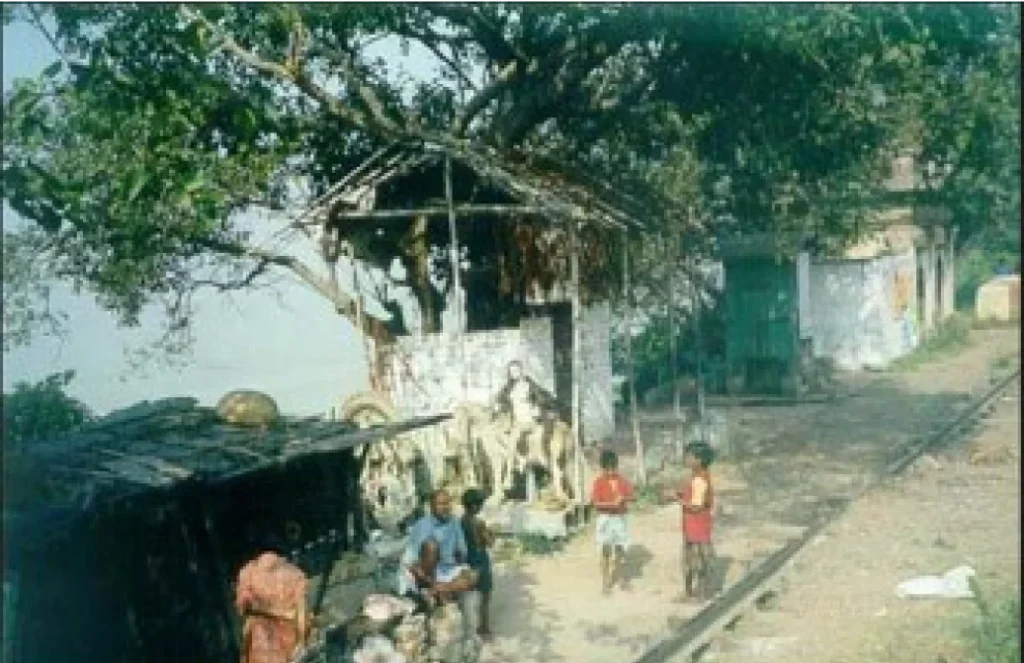

Economic

(Source : Sukrit Sen)

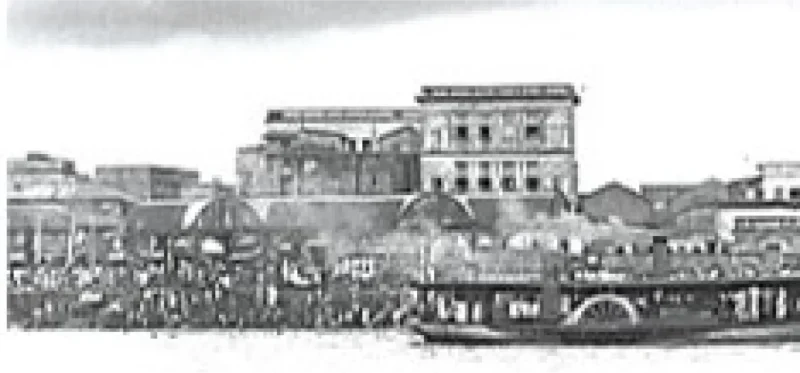

Transport

(Source : Sukrit Sen)

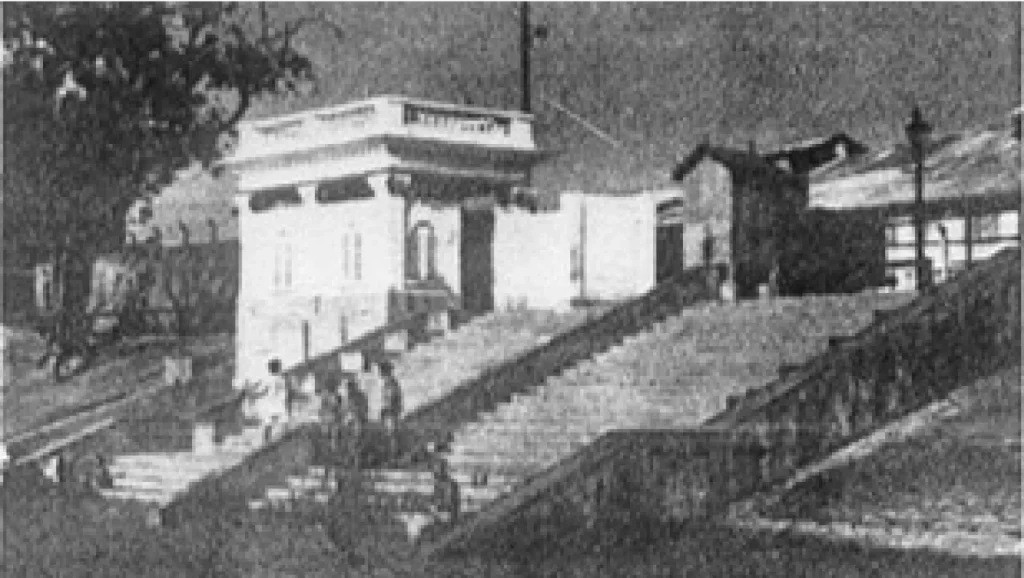

Home to Homeless

(Source : Sukrit Sen)

Recreation

(Source : Sukrit Sen)

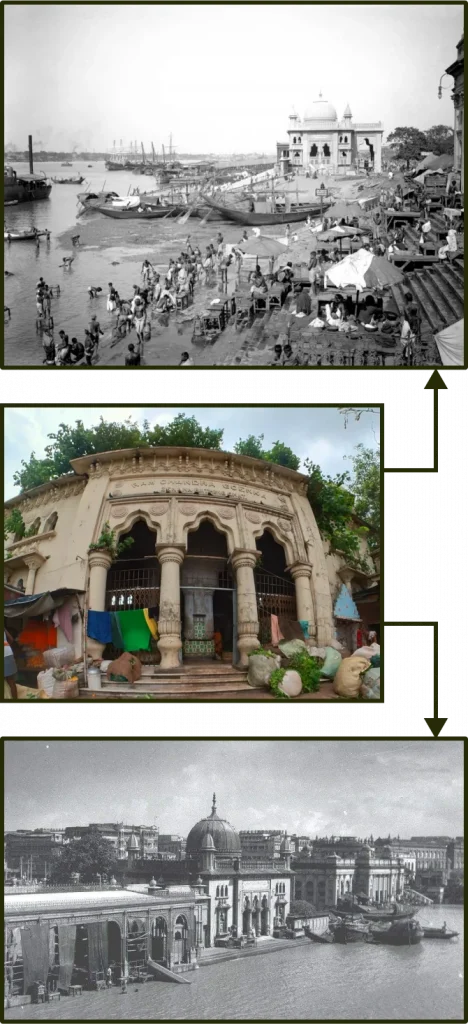

Ghatscape through drifts and decades

The ghat-pavilions were commissioned mainly by prominent personalities of the time, different ethnic groups, businesses, or trade organizations, and were named after their patrons.

Then

Now

Then

Now

Chhotelal Ghat ki Ghat – 1875 (PC: Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS) 1912-14) 2019 (PC: Soumik Sarkar)

Then

Now

Ram Chandra Goenka zenana Bathing ghat – 1890 (source: Old Indian Photos) ;

2021 (PC: Sreyosi Pramanik)

Then

Now

Chand Pal Ghat – 1770 (painting by James Baillie Fraser, 1826) ;

2023 (Wikipedia Commons)

Then

Now

Jagannath ghat – late 19th c. (source: Wikimedia Commons) ;2021 (source: Wikimedia Commons)

Then

Now

Mallick ghat -1855/ 1874 (source: Wikimedia Commons/ Bourne and Shepherd, c.1880’s) ;

2023 (PC: Sarthak Paul)

Then

Now

Ahiritola ghat – late 19th c. (source: Wikimedia Commons) ;

2023 (PC: YouTube)

Then

Now

Babu Raj Chandra Das ghat or Babughat – 1830 (adjacent to Chand pal ghat) (source: noisebreak.com) ; 2019 (source: http://double-dolphin.blogspot.com )

Ghatscape: people, events, associations, and memories

The ghatscape holds a collection of cultural narratives that bear witness to numerous pivotal moments in the city’s history. The growth and decline of the ghats are intertwined with the evolution of the riverfront and the intricate historical development of the city. These ghat functions provide a glimpse into the socio-cultural and economic scenarios of the then ‘Calcutta’ and its affluent and elite persons, also known as ‘Babu.s’.

Mayer Ghat

Mayer Ghat is the northernmost ghat after the Bagbazar canal and this was frequented by Sri Sri Ma i.e., Holy Mother SaradaMoni Devi for her daily bath during her stay at Mother’s House, Bagbazar between 1909 to 1920 till her mahasamadhi. The route taken by her is indicated in the map. Previously known as Durga Charan Mukherjee Ghat, it was renamed as ‘Mayer ghat’ in her honour.

‘Mayer Ghat’ is also a success story in rejuvenating the ghat area, restoring the historic pavilion, and in the process, the environment. Steered by the local community, it was led by the Ramakrishna Math- Bagbazar in 2004. The scheme prepared by the Architecture Dept., JU was implemented with active participation of all public stakeholders – KMC, Eastern Railways, KoPT, Kolkata Police, CESC, and public representatives- local MP & MLA.

Chhotelal ki Ghat

Designed by the British architect Richard Roskell Bayne, Chhotelal ki ghat (1875) remains the most photographed ghat-pavilion of that era. An iconic landmark in its own right and the centre of public attention of its time, it was but natural for putting up plaques in public interest / viewing on its body. One such tragedy remains recorded on the walls of this ghat-pavilion as a historic marker.

As there was no rail linkage to Puri Jagannath Dham during the late 19th century and walking was too strenuous, many pilgrims, especially women, preferred to take the river route to reach Puri. McLine and Co. ran a steamship named ‘Sir John Lawrence’ from Calcutta to Chandbali (River Baitarani, Bhadrak, Orissa) for the Puri pilgrims.

Tragedy struck on 25th May 1887- the steamship drowned in the sea with all its passengers due to a cyclonic storm. A commemorative plaque is installed on the pavilion’s south wall to mark this tragic event. It reads as follows:

“The stone is dedicated by a few English women to the memory of those pilgrims, mostly women, who perished with Sir John Lawrence in the cyclone of 25th May 1887”.

Courtesy: British Library

(PC: Sarthak Paul, 2023)

Ghats as gateways & transport terminals to the erstwhile Calcutta

Chand Paul Ghat

Named after one Chandra Nath Pal, keeper of a small shop at the ghat, Chandpal Ghat was in existence since 1774 on the southern boundary of the then Dihi Calcutta (Ray, 1902).

With the new Fort William coming up in 1781 and the area in between cleared off the jungles, the ghat became the landing place for all the who’s who of the time- British Governor Generals, Commanders-in-Chief, Judges and Bishops, including Sir William Jones in 1783 and James Prinsep in 1819.

It was also from this ghat that Sri Aurobindo sailed to Pondicherry by the French ship SS Dupleix (Sri Aurobindo Institute).

Babughat

Babughat with its pavilion was constructed in memory of Babu Raj Chandra Das by his wife, the honourable Rani Rasmoni in 1830. This became a widely used embarkation / disembarkation point for the river traffic.

On 30th December 1841, Mother M. Delphine Hart and 11 Loreto nuns from Ireland landed at Babughat. Bishop Carew welcomed them at Calcutta. Loreto House, the first Loreto school in India, was established at 5, Middleton Row on 10th January 1842 by the Sisters. Loreto Convent School, Entally was started in 1843.

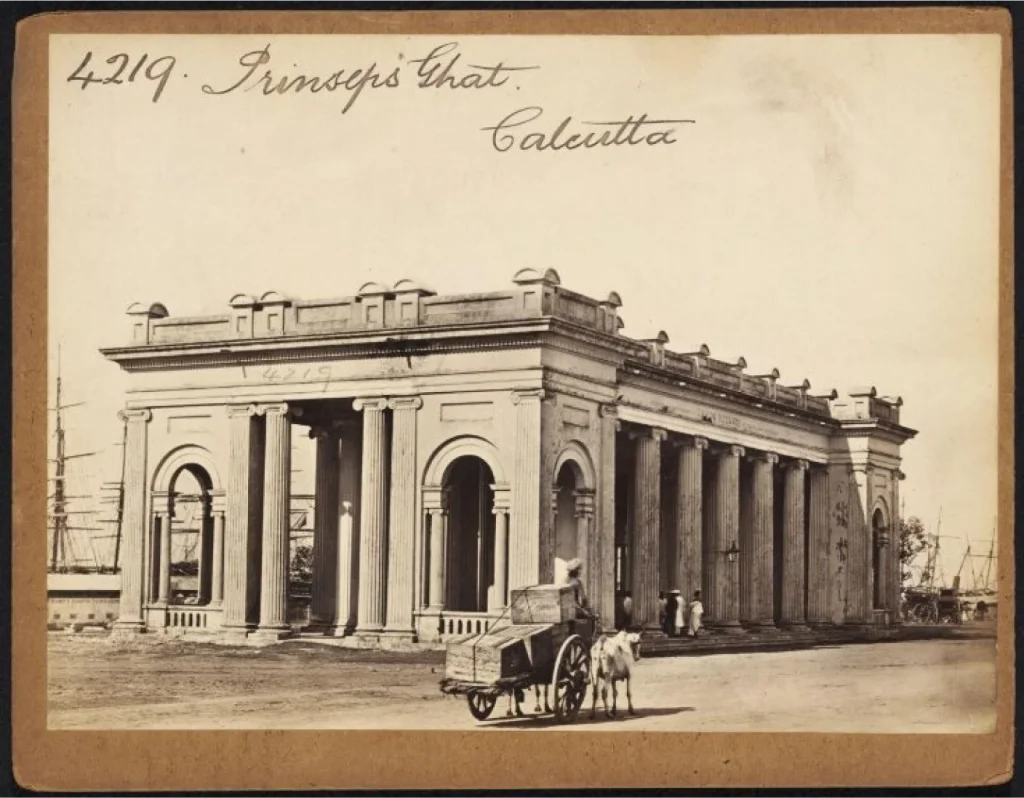

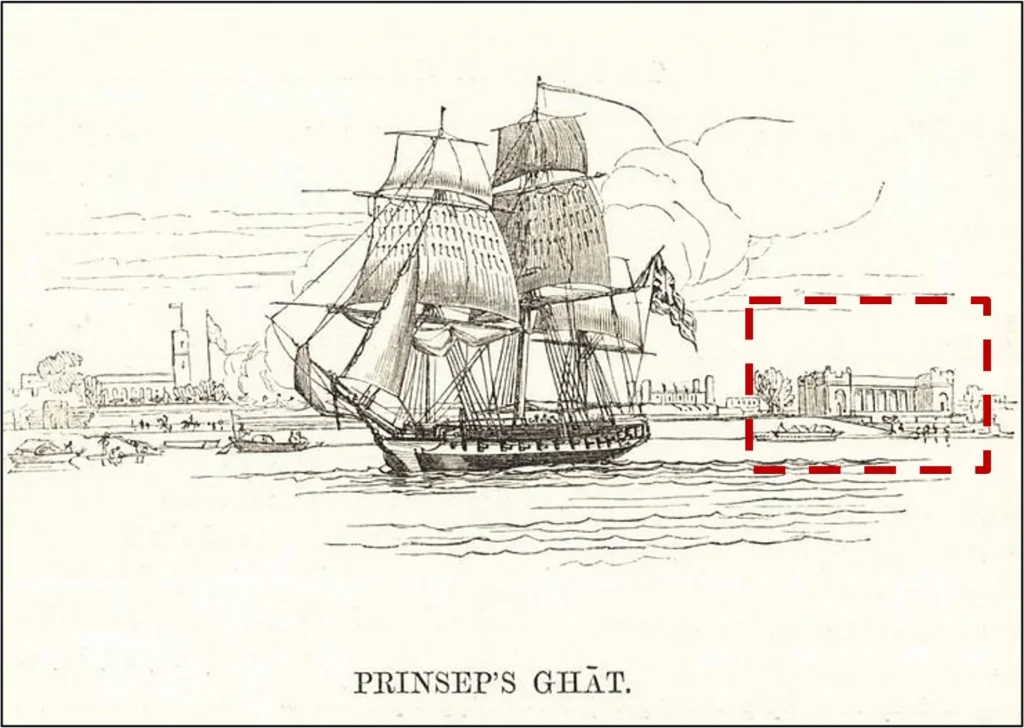

Prinsep Ghat

This memorial ghat structure was completed in 1843 as a tribute to James Prinsep (1799-1840), an eminent scholar, orientalist and antiquary.

The architecturally elegant ghat-pavilion soon became the preferred landing place for the British dignitaries, till the sea-river transport were in use. It witnessed the arrival of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales and the eldest son of Queen Victoria In 1875, Prince of Wales (later King George V) in 1905, and the British royal family in 1911.

The memorial pavilion is now about 100 m inland from the riverbank.

JUXTAPOSITION OF FORM AND STYLE

The ghat-pavilions are a testament to the diverse architectural styles that reflect Kolkata’s cultural richness.

Ghat construction activities spread over a span of nearly 200 years display different styles and scales in the pavilions.

Babughat (1830) with pediment supported by Doric columns, and Prinsep Ghat Memorial (1843) with Ionic columns, follow distinct European architectural style. Kumartuli ghat, Nimtala ghat, Champatala ghat, and Adya Shraddha ghat etc., are mostly square-shaped masonry structures with elements of Indian architecture, while some ghat-pavilions like Jagannath ghat and P.K. Tagore ghat are Cast-Iron structures.

The most iconic Chhotelal ki Ghat (1875) presents impressive elevations with stately Corinthian columns, arches, and a raised central drum that got obscured due to an incoherent vertical expansion in the late 1980s.

Ram Chandra Goenka Zenana bathing ghat (1890) is another grand structure, albeit in mixed-style, with more graceful arches, a central dome and chhatri-like turrets at the four roof-corners.

Mutty Lall Seal ghat pavilion (1840) seems quite ahead of its time, with tall arched openings and flat-roof entablature held by imposing Corinthian columns.

Current challenges

The ghat-pavilions, with their splendid architecture, have lost their meaning today. Once standing as grand gateways, these are now relegated to the backyard, as is the river. Although their relevance for holy bathing and ferry terminal continues well, the cultural and recreational values are almost lost. Even though most of these ghat-pavilions being declared Grade I heritage structures, these have fallen victim to incompatible uses like encroachments, vehicle parking, night shelter, and commercial activities. The Circular Railway corridor adds to the woes by fragmenting the riverfront. Environmental issues like plastic pollution of the ghats and river-front further aggravate the complexities.

(PC: Sreyosi Pramanik, 2021)

Conclusion

We imagine a riverfront that is accessible to all and which, punctuated by these unique ghat-pavilions will narrate the story of this more than three-hundred-year-old city, its layered history, its triumphs and tragedies, its people and palaces, its classes and masses, and its immensely significant role in the Independence movement of our country.

Mayer ghat in the city’s north and Prinsep ghat in the south give us hope that other ghat-pavilions can be restored, their old glory revived, and the ghat adjacent area can become a hub of recreational and cultural activities.

References

- Bardhan, S. and Paul, S. (2023), The cultural landscape of the Bhagirathi-Hooghly riverfront in Kolkata, India: studies on its built and natural heritage, Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development, Vol. 13 No. 2, pp. 219-237. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCHMSD-08-2020-0119.

- Bardhan, S. and Paul, S. (2019), Envisioning an eco-cultural urban landscape Studies on the Ghats of the River Bhagirathi-Hooghly in Kolkata, India, IFLA CL WG’s International Symposium on Historic Cultural Landscapes: Succession, Sustenance and Sustainability, Seoul, 18-20 Nov. 2019.

- Bardhan, S. (2006). Riverfront rejuvenation: ‘Mayer Ghat’ in North Calcutta. Journal of Indian Institute of Architects, 71(8). pp. 43.

- Jadavpur University. 2003-04. Study & Documentation of Ghat Structures Along Calcutta Riverfront – A Study conducted by students of Department. of Architecture, Jadavpur University, Kolkata. Unpublished.

- Kundu, A.K. and Nag, P. (1996), Atlas of the City of Calcutta and its environs, National Atlas & Thematic Mapping Organisation (NATMO).

- Mitra, R. and Mitra, R. ‘Saswata Kolkata’ Part I- ‘Gangar Ghat’

- Motilal, A. Howrah – Kolkatar Gangar Ghat’.

- Mukhopadhyay, A. (2018), “MullickGhat and the Jagannath steamer ghat”, available at: https://puronokolkata.com/2018/08/22/mullick-ghat-and-the-jagannath-steamer-ghat/ (accessed 29 December 2020).

- Mukhopadhyay, H (1915), Kalikata Shekaler O Ekaler. Kalikata Sekaler O Ekaler – Harisadhan Mukhopadhyay / কলিকাতা সেকালের ও একালের – হরিসাধন মুখোপাধ্যায় : Bangla Rare Books : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

- Old Indian photos (accessed April 2023),article

- Ray, A.K. (1902), Census of India, 1901, Vol. VII- Calcutta, Town and suburbs, Part-I, A short history of Calcutta, Bengal Secretariat Press, Calcutta.

- Sri Aurobindo Institute (accessed May 2023), Departure to Pondicherry – Sri Aurobindo (1906-1910)